In this post: the features I love most about Java in 2025, and the wishlist I’d submit for the next 30 years.

Happy Birthday? 🎈

I have written Java code for most of my professional career. On 23rd May 2025, it celebrated its 30th birthday. The language is older than I am, and has undeniably stood the test of time.

Yet, in most development circles it gets a rather negative reception. Despite infamously powering “over 3 billion devices” and providing the secret sauce for some of the world’s biggest companies, it is still seen as verbose and complex. This isn’t controversial - there are enhancement proposals dedicated to making Java a nicer language to learn.

As with everything in technology, you need to use the right tool for the job, and there are paradigms that even modern Java can’t live up to. That said, its recent developments have taken a lot of great features from other languages and given it a fresh lease of life.

As we celebrate 30 years of the language, this blog post will explore some features I particularly admire, as well as a “wishlist” of features I have come across in other languages that would prove a very neat JEP in a future release.

Image credit: JetBrains

Image credit: JetBrains

Java in a Nutshell 🌰

Earlier I spoke about the “right tool for the job” mantra. Being a general-purpose, Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) language, there are many use cases that Java is great for:

- Web Applications (Microservices): Servers which can cope with many thousands of requests using normal multi-threading or reactive frameworks. Simple HTTP applications can be built without frameworks, but enterprise-scale systems may benefit from using Spring, Quarkus or Micronaut.

- Enterprise: Traditional industries like banking and finance rely on a rich ecosystem of support for distributed APIs, queues, cryptography and persistence (JDBC).

- Mobile Applications: Benefitting from its cross-platform “write once, run anywhere” tagline, Android applications primarily run on the JVM, via Kotlin or Java.

- Gaming: Applications like Minecraft and Runescape.

- Big Data: Streaming technologies like Apache Kafka, Hadoop and Flink are all Java. Column stores like Apache Cassandra are also Java based. Large datasets can be explored using Elasticsearch, which is also (you guessed it!) Java.

That said, it requires more ceremony than other languages, which makes it a less popular choice in the following domains:

- Latency-sensitive applications: If manual memory management is important for performance, C++ or Rust is a far superior choice. Despite recent innovations with the Java Garbage Collector (e.g. zgc) and start-up times (e.g. CRaC and GraalVM), Java suffers more than most languages due to heavy-GC pauses or cold starts in serverless environments.

- Scripting: For cron jobs or CI/CD integration, just use Python, or (even better) Bash.

- Data manipulation: It takes a lot of code or third party libraries to manipulate data in common formats (e.g. CSV, JSON) and apply transforms. Using

pandas,numpyorscipyis more intuitive. - AI and ML: Despite recent innovations (e.g. LangChain4j), the bulk of community contributions to these fields are in Python.

- Web UIs: You will be hard-pressed to find anyone willing to pick a fight for Swing or JavaFX over React, Angular or Next.js. For desktop applications, there is a bit more of a debate, though it is largely used in the IDEs themselves.

Powerful features ⚡️

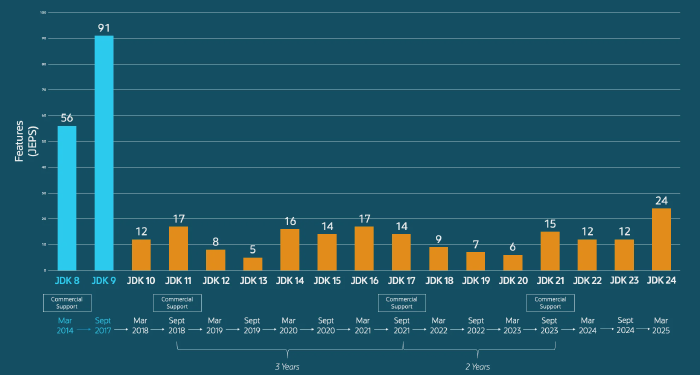

It goes without saying the impact that Java 8 had in 2014 was huge. Many people still describe it as the most revolutionary release we have had in the last 15 years.

default methods blurred the line between Interfaces and Abstract Classes, but have proven very useful in the production code I have shipped, such as when rolling out a new method on an existing API.

Lambdas, Streams and Optionals pushed Java into the functional domain more aggressively than ever, where it has been solidifying its place since.

In most production code, we don’t want side effects when we manipulate objects, and we want to capture data in composable but deconstructable patterns. This philosophy has given us records, sealed classes and powerful pattern matching semantics. It is great that one can now fully exhaust all options in a switch statement without falling back to a default case and blowing up.

Use of var is controversial in some circles (we weren’t always duplicating type definitions both sides of the assignment). That said, IDEs’ type inferences have made the transition easier to manage.

Virtual threads provide a nice solution to tackle I/O intensive applications. In today’s distributed world, I/O makes up a significant portion of most blocking code. Calling an HTTP endpoint, making an SDK call, executing a database transaction. All of these situations benefit from swapping out executors for ones which spin up virtual threads rather than platform threads. Just make sure you learn from others’ mistakes!

In the near future, Stream Gatherers will provide to intermediate operations what Collectors did for terminal operations. Whilst map, filter and reduce have been core staples of the Streams API for years, there are other useful execution paths. Window functions or stateful scans (e.g. moving averages or deduplication) to name a few.

I am yet to be fully convinced on unnamed variables (_) as I worry they will impact readability, but I am sure time will win me over like it did with var.

| Java Version | Features |

|---|---|

| 8 | Lambdas, Streams, Optionals, Functional Interfaces, default methods |

| 9 | Modules, JShell |

| 10 | var keyword |

| 11 | HttpClient |

| 12–16 | switch expressions, Text blocks |

| 17 | record, sealed classes, Pattern matching with instanceof |

| 21 | Virtual threads, Pattern matching with switch |

| 22+ | Stream Gatherers, Unnamed variables (_), Statements before super |

Image credit: InfoQ

Image credit: InfoQ

Feature wishlist 💡

Despite boasting an impressive list of recent and planned JEPs, there is still room for the language to grow. Based on my experience with other languages, there are a number of features that require a lot of boilerplate to support in Java. Native support for any of these would be welcome additions.

Disclaimer ⚠️: This is my opinion as a language user working in an ideal world. I realise that most of this would require large overhauls and break backwards compatibility.

Enhanced Data Classes

Immutable data classes finally came to Java with the advent of records. With a record, we have getters, hashCode(), equals() and toString() out of the box.

This is enough to deconstruct objects into their properties during switch statements, which is coming soon. A natural extension to this would be support for validation, default values and serialisation options.

Projects like Lombok and Joda-Beans have aimed to bring this richness to Java for years, with limited adoption.

A sketch of what this could look like is below - a data class with built-in validation and explicit support for JSON serialisation. This feature would accelerate most standard API development without requiring JsonObject or Gson.

public record Person(

@NotBlank String firstName,

@NotBlank String lastName,

@NotNegative Integer age) implements Serializable<Json> { }

Map Streams

Since Java 8, we have been able to stream and process data collections. This is readable and very effective for simple collections like List or Set. However, Maps are not as easy to visualise in a Stream - we must use their entrySet(), which means reasoning about a Map.Entry at every step of the stream.

OpenGamma’s Strata project provides a full implementation (sketched below) of what first-class Map support in Streams could look like.

public final class MapStream<K, V> implements Stream<Map.Entry<K, V>> {

private final Stream<Map.Entry<K, V>> underlying;

public static <K, V> MapStream<K, V> of(Map<K, V> map) {

return new MapStream<>(map.entrySet().stream());

}

public <R> MapStream<K, R> mapValues(Function<? extends V, ? extends R> mapperFn) { /* Omitted */ }

public <R> MapStream<R, V> mapKeys(Function<? extends R, ? extends V> mapperFn) { /* Omitted */ }

public MapStream<K, V> filterKeys(Predicate<? extends K> keyPredicate) { /* Omitted */ }

public MapStream<K, V> filterValues(Predicate<? extends V> valuePredicate) { /* Omitted */ }

public abstract Map<K, V> toMap();

}

Explicit Mutable Collections

Kotlin does a very good job at providing immutability by default. Users are encouraged to use val by default, before falling back to var.

By extension, users have to opt in to mutable collections with the below factory methods.

mutableListOf("1", "2", "3")

listOf("1", "2", "3")

Java collections are mutable by default. List.of(...) and Set.of(...) use unmodifiable collections but do not make this obvious enough.

Delegate Methods

It is a common pattern that we want to wrap an implementation of an interface in another. For example, a caching or rate-limiting implementation which wraps an underlying service. This separation of concerns is extremely powerful. To follow this pattern in Java, we must define a full implementation even if the behaviour we are overriding only applies to a subset of the methods. In Kotlin we can avoid the boilerplate, by using delegates.

interface Greeter {

fun greet()

fun farewell()

}

class SimpleGreeter : Greeter {

override fun greet() = println("Hello!")

override fun farewell() = println("Goodbye!")

}

// Partially override: only 'greet' is customized

class CustomGreeter(private val greeter: Greeter) : Greeter by greeter {

override fun greet() = println("👋 Custom Hello!") // overrides only this

}

fun main() {

val greeter = CustomGreeter(SimpleGreeter())

greeter.greet() // prints: 👋 Custom Hello!

greeter.farewell() // prints: Goodbye!

}

String Templates

When constructing large bodies of text, Java’s multi-line text blocks have been a great addition.

However, they are only readable if the full body of the text is static. Otherwise, we are forced to use String.format(...) to interpolate values, which is hard to read when using many injected values.

String Templates were briefly previewed in the JVM, but later removed. I do hope that something like this comes to the language in a future release. In Kotlin (amongst other languages), we can place values directly where they are used.

val payload = """

{

"firstName": "$firstName",

"lastName": "$lastName",

"age": "$age"

}

""".trimIndent()

List Comprehension

Despite being harder to debug in long chains of calls, declarative Streams are more often than not easier to read than the imperative equivalent.

However, a lot of Streams are a variant of map and filter (or vice versa). I do wonder if we could borrow comprehensions from Python to make this a readable single line operation.

class_id = '123'

class_info = _get_class_info(class_id = class_id)

mature_students = [person.name() for person in class_info.members() if person.age() > 21]

Tuples

There are lots of occasions where we might wish to work with a Pair or Tuple of values for data manipulation and extraction, without declaring an entire class for them. OpenGamma’s Strata has Pair and Tuple for this purpose, to make up for lack of support in the language.

In Python, one can declare a namedtuple with minimal ceremony and use them within the desired scope of the application.

Account = namedtuple("Account", ["account_id", "account_name"])

def get_eligible_accounts() -> List[Account]:

all_accounts = _fetch_accounts()

return [Account(account_id=a.id, account_name=a.name) for a in all_accounts if a.type == 'Primary']

Named Parameters

When calling methods accepting the same type in multiple places in its signature, I believe named parameters would make life much easier and avoid ambiguity. Especially in environments where type inference is not available.

full_name = _get_full_name(first_name = "Chris", last_name = "Davies")

def _get_full_name(first_name: str, last_name: str) -> str:

return f"{first_name} {last_name}"

Nullable Types

null references were once described as the billion-dollar mistake. Indeed, Java makes it very easy to obscure when values could be null.

Despite the best efforts of the Optional type, it just isn’t suitable for use everywhere. It is a great solution when returning values, but not as we pass them around the application.

By explicitly marking an object as a nullable type variant, we can enforce checks in the IDE which tell a programmer when a null reference has not been accounted for. Various annotations exist to hint that types could be null or not null, but they are not doing static code analysis on the same level as other languages.

data class UserProfile(

val id: Int,

val name: String,

val email: String?, // Optional — user may not provide one

val dateOfBirth: LocalDate?, // Optional — user may skip it

val bio: String? = null // Optional with default value

)

fun printProfile(profile: UserProfile) {

println("User ID: ${profile.id}")

println("Name: ${profile.name}")

println("Bio: ${profile.bio ?: "No bio yet"}")

println("Email: ${profile.email ?: "Not provided"}")

profile.dateOfBirth?.let {

println("Age: ${Period.between(it, LocalDate.now()).years}")

} ?: println("DOB: Not provided")

}

Typed Strings

In many APIs we want to enforce a domain over our identifier types, instead of letting them be free-form Strings.

TypeScript brings type and set theory to the forefront of the language’s design, which means it can do neat things like the below. AccountId and TransactionId are still treated as string, but require very minimal declaration to bring safety to our APIs. No more passing in the wrong string values everywhere.

type AccountId = string & { readonly brand: 'AccountId' };

type TransactionId = string & { readonly brand: 'TransactionId' };

class AccountService {

deposit(transactionId: TransactionId, accountId: AccountId, amount: number, description: string): Transaction {

// ...

}

}

Result Types

A large part of the negative perception Java gets is due to Checked Exceptions. It is indeed clunky that a method might bubble up an Exception through many calls, forcing application programmers to handle it.

In Go, methods may return multiple objects, which allows us to check for an Error. The code block if err != nil is commonly seen as a result. Users are explicitly forced to consider that a return type could be an error at the call site, without bubbling it up further.

TypeScript has true-myth for a similar purpose. OpenGamma’s Strata has Result, which looks like the below.

A native addition to the Java language would be welcome here. In most cases we want to face errors head-on.

public class Result<R> {

private final R value;

private final Failure failure;

public static <R> Result<R> of(Supplier<R> callFn) {

try {

R value = callFn.get();

return new Result<>(value, null);

} catch (Exception ex) {

return new Result<>(null, new Failure(FailureType.ERROR, "Error executing function", ex));

}

}

public boolean isSuccess() {

return value != null;

}

}

Decorators

This section is largely about “syntactic-sugar”. With Functions, annotations and Aspect-Oriented Programming through frameworks like Spring, Java could support this kind of behaviour. However, the ability for everyday programmers to make use of those tools is limited.

Alternatively, Python supports a neat concept which allows users to wrap the execution of a method in custom logic, which can be done for abstracting performance logging/metrics, or other kinds of validation.

def timer(func):

"""Print the runtime of the decorated function"""

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper_timer(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

value = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

print(f"Finished {func.__name__}() in {run_time:.4f} secs")

return value

return wrapper_timer

@timer

def waste_some_time(num_times):

for _ in range(num_times):

sum([number**2 for number in range(10_000)])

Aside: Why does Java still beat other JVM languages’ popularity? 🤔

A natural question might be: “If Java has largely copied its recent good features from other JVM languages, why did it not get replaced by them?”.

Indeed, recent polling shows that it is standing strong compared to Kotlin, Scala, Groovy etc. An esteemed colleague of mine – Stephen Colebourne – summarizes this far better than I ever could wish to in his 2024 Devoxx talk.

TL;DW (Too Long; Didn’t Watch)

Had Kotlin been quicker to adopt a v1.0, we might all be writing Kotlin code today instead of Java.

Summary 🧵

This post explored the state of Java at 30. From the powerful features I admire to a “wishlist” of future JEPs. With the success of the 6-month release cadence, the language keeps evolving while maintaining strong backward compatibility.

Regardless of whether you think we will be discussing its 50th or 60th birthday in years to come (Spoiler: we definitely will), it is a very impressive piece of technology. I look forward to seeing how the language grows in the next 30 years.

Get in touch 📧

As I say in my About page, I would love to hear from you. If you got to the end of this post and have anything to share, please get in touch on LinkedIn or Twitter.