Figma’s recent S-1 filing was called out in a flurry of headlines for declaring a spend of "$300,000 a day" on AWS. At face value, that number seems shocking, but perhaps the industry reaction itself is the main thing worth examining.

Many organizations subscribe to the “you build it, you run it” operating model, but this ownership rarely extends to costs. When was the last time your pager went off in the night because a service experienced an unusual spike in costs? ☎️🧑🚒

In this post, we look at:

- Why costs are a shared responsibility.

- What developers (and tooling providers) can do to help own them early on.

- The vendor “lock-in” trade-off.

This post was largely inspired by SigNoz’s post: “Observability isn’t just for SREs”.

FinOps 💰

Cost management can often feel far-removed from an engineer’s remit. The reality is, behind staffing costs, hosting costs are one of the biggest line items for a business, and FinOps is one of the few engineering disciplines where you can know your impact on the bottom line within 24 hours.

Companies like 37signals have been vocal about their cloud exit, presumably feeling like this when it came to paying the invoice.

Companies like 37signals have been vocal about their cloud exit, presumably feeling like this when it came to paying the invoice.

Figma’s reported daily spend immediately becomes a moot point when you hear that they are running with a 91% gross margin and their infrastructure spend is only 12% of their revenue. They have been public about the many ways they have reduced cloud spend. Thankfully, a lot of the noise was debunked by prominent voices such as Corey Quinn. The reaction is interesting though - do engineers really know what a reasonable hosting cost is at their organization, or what gross-margin is?

Availability often trumps Costs (🧑🚒 > 💸)

It is understandable why many organizations implicitly prioritise availability over costs in their definition of “owning” a production system.

- Visibility: The former is immediately visible to clients, so does not carry as much immediate reputational damage.

- Complexity: It is easier to reason about. An SLA is a static target. Costs are dynamic - each part of the system’s spend may correlate with different factors (e.g. scheduled bursts or spikes due to system activity).

- Maturity: Startups desperately need market fit before they can set up a rigid FinOps strategy. If growth is sufficiently high in the early stages, costs are less of a concern.

- Cost: The ironic one - engineers are expensive, so having them purely focus on this is sometimes not viable.

Despite feeling like orthogonal concerns, several concepts we use to describe availability could also carry over into the FinOps space.

| Availability 🧑🚒 | FinOps 💸 |

|---|---|

| SLA | Target spend - a fixed $ value, or % of revenue. |

| Alert | A budget breach or anomaly alarm. |

| MTTD | Mean time (duration) to detect a cost spike. |

| MTTR | Mean time (duration) to recover from a cost spike. |

| Incident | An investigation into an unexplained cost. |

| Observability | Cost and usage reports/dashboards. |

Conway’s Law: A limiting factor? ⚖️

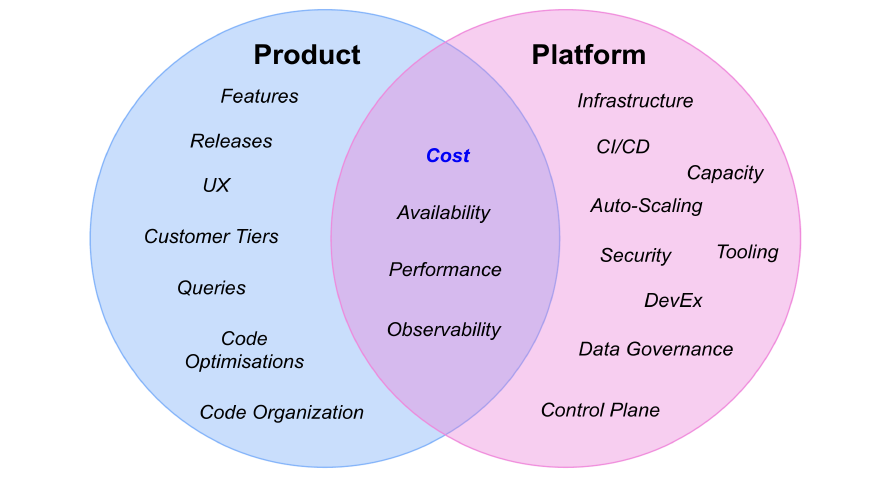

Many organizations choose to divide teams into Product and Platform responsibilities as a way of creating abstraction. As Conway’s Law describes, a system architecture will become a representation of the organization structure. This results in situations where developers shipping features often do not understand the infrastructure that their code runs on. Greater abstraction means freedom at the infrastructure level, but also means less scrutiny on hosting costs for developers who aren’t operating at that level of the stack.

The key trade-off in these team boundaries, is that many meaningful cost optimization opportunities arise in the intersection of what Product and Platform Engineering teams can achieve alone. If the responsibility to optimise costs lies with a central team, the goal becomes a moving target as micro-level decisions elsewhere slowly negate the impact of planned work. Efforts significantly reduce if a culture of awareness/ownership exists across teams.

A simplified model - responsibilities will vary by org, with impactful efforts sitting in the overlap.

A simplified model - responsibilities will vary by org, with impactful efforts sitting in the overlap.

Optimisations require partnership 🤝

In a series of projects spanning a few quarters, we managed to reduce our AWS spend by 40%. This was no mean feat, but a key lesson was that every optimisation required communication between Platform and Product teams. Whether gathering data, getting buy-in or keeping teams in the loop in case of unexpected outages.

Life is also made significantly easier if Product-focused teams can readily help explain ongoing cost changes (e.g., a new client onboard, a recent feature rollout etc.). If revenue increases proportionally, it becomes less of a concern and budgets can be adjusted to the new baseline.

Let’s look at some common types of optimisation, and the level of their cross-team dependencies. These are placed in order of increasing dependency on Product context, to squeeze the most value out of each optimisation. Click to expand/collapse each one.

Settings ⚙️

Settings which are low-effort to change, and should arguably be defaults. Once enabled, they are immediately effective.

e.g.: Using intelligent tiering, bucket encryption keys, different architectures (e.g. Graviton), log classes.

Dependencies: Co-ordination is needed during testing and rollout to minimise impact on production environments.

Cleanup 🧹

Reducing the footprint of compute services and managing the lifetime of data.

e.g.: Removing unused services, adding lifecycle policies, TTLs, job timeouts.

Dependencies: Much like Hyrum’s law for APIs, it is almost never clear which service or data is relied upon until it is deleted. Product teams can provide context on which service/data is valuable and for which initiatives/clients far quicker than metrics would alone. Metrics tell you the current state of the world - not what to expect in the near future.

Right-sizing 🤏

Matching the reserved capacity of compute services as closely to their usage as possible.

e.g.: Changing CPU and memory (statically or dynamically), removing redundant instances, adopting serverless.

Dependencies: If embracing serverless, there are fundamental limitations (e.g. memory, timeouts) that Product teams need to know about when shipping code. Right-sizing might mean use of horizontal or vertical scaling, which means choosing a sensible scaling strategy (e.g. scheduled, on-demand). This all requires crucial Product context.

Re-architecting 🎲

Changing the operating model or system architecture of a service, accepting a reasonable trade-off (e.g. performance, availability) for a significant cost reduction.

e.g.: Embracing event driven architecture (EDA), removing middleware (e.g. queues/load balancers/proxies), using Spot compute.

Dependencies: Adopting EDA might add integration latency at key points in a customer workflow. Using interruptible batch jobs could delay critical outputs if there is no checkpointing in use when the job restarts. Metrics can help guide decisions on how often middleware services add value, but Product context is needed to assess whether they are needed long-term. What might seem overkill for today’s scale might be perfectly sensible for an upcoming initiative.

Code changes 🧩

Modifying the behaviour of application code to alter its usage of resources (e.g., databases, storage, APIs).

e.g.: Caching, “pushing down” data filtering, changing storage/API access patterns, reducing logging.

Dependencies: Often the hardest optimisations for Platform teams to spot if relying on infrastructure metrics alone. An isolated measure of CPU/memory usage or database accesses will not tell you whether there is room to meaningfully optimise behaviour. This is where an observability stack of Logs, Metrics and Traces matters. Everyday code changes can introduce large changes in the cost-profile of a service. Shifting left is even more important at this level (discussed below).

Shifting left ⏪

So far, we have only touched on optimisations once costs are already a problem. With greater ownership across teams, we can shift a lot of these concerns “left” earlier in the development cycle, to reduce the size of future problems. Not every developer needs to take on large, multi-week optimisation projects to be seen as “owning” costs.

A sad irony is that getting visibility into costs itself carries a cost (through additional services and SaaS subscriptions), but the payoff is often worthwhile.

Observability 📊

Giving teams visibility of their baseline costs is the first step. If using a cloud provider, a lot of these primitives are provided:

- Tagging: Label infrastructure by team/project. Regularly monitor Cost Explorer dashboards (e.g. AWS/GCP/KubeCost) and schedule reports.

- Alerting: Set up budgets and anomaly detection, with integrations to the communication platforms (e.g. Slack & incident.io).

- Dependencies: Monitor usage metrics for each third-party provider / service / API that has its own pricing model.

Once observability is in place, let’s look at some practical methods that enable cost ownership earlier on in development.

Designs 🎨

During the design of a new service or feature, ADRs (Architectural Decision Records) could explicitly consider the cost impact of decisions - forcing early discussion. Whilst it is tricky to provide exact dollar estimates, a “back of the envelope” calculation is made far easier by cloud providers’ Pricing Calculators. In the age of AI and LLMs with spiralling costs there, there are even token calculators!

A mental model I like to use for Cloud costs is:

Compute = (Capacity * Time)Storage = (Retention * Data Size) + Data TransferredLogging = (Retention * Event Count * Event Size)

Tooling 🛠️

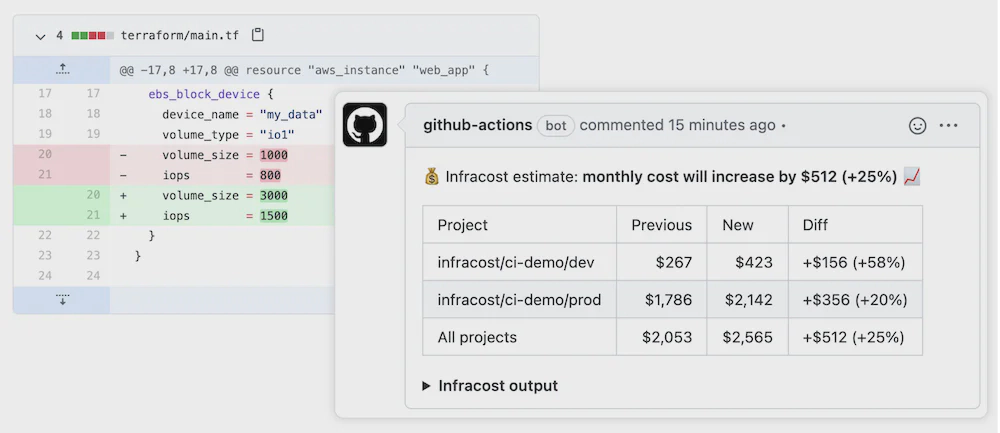

A range of tooling exists to target the IDE and Pull Request workflows, which developers can use to estimate and reduce cost impact before code is shipped.

For infrastructure changes, tools like Infracost offer comparisons in the IDE and PR reviews. At the application layer, I’ve had some success using Datadog’s IDEA plugin to remove noisy logs and optimise frequently executed code. There is room for vendors to go further in this space, and bring cost awareness to the IDE for application code.

Image credit: Infracost

Image credit: Infracost

Artificial Intelligence 🤖

As AI tooling like Claude Code and CodeRabbit start to integrate into CLI/IDE and VCS software, there is a natural space to ensure costs are considered with every prompt.

Amazon’s Kiro is an interesting proposition here. Providing “spec” documents and breaking tasks down like a human before code is generated would naturally lend itself to feeding in ADRs like those described above. If a file exists in the repository describing the system’s tenancy model, budget and priorities as a system prompt, then the code these tools generate could reflect that.

“Lock-in”: Friend or foe? 🔐

The final topic we will touch on here is vendor “lock-in”. A lot of the scrutiny on Figma’s IPO filings came from their $545m-per-year multi-year commitment to AWS. By admitting their reliance on a sole provider and solidifying plans to spend across a long-term horizon, it was seen by many as a big concentration risk.

As Corey Quinn points out, that size of commitment may be risky for a company hosting “lifted and shifted” VMs where compute costs come at a premium, but Figma’s technical stack is deeply ingrained in AWS ecosystem already. Once you are far enough along the adoption curve of a particular cloud provider, it leaves a lot of money on the table if you do not make commitments. This could be explicit commitments via Savings Plans/reserved capacity, or implicit ones like moving “glue code” to the infrastructure layer. The latter can save many Engineering hours, in return for greater dependence on a specific provider’s primitives.

One of my go-to talks from recent AWS re:Invent conferences is about Serverless Refactoring, which blurs the line between application and infrastructure concerns.

TL;DW (Too Long; Didn’t Watch)

The next time you find yourself writing code to integrate two pieces of infrastructure, it’s worth questioning if a different primitive exists instead.

Summary 🧵

This post tried to cover a lot of ground. Here are my main takeaways:

- 💸 Costs are a shared responsibility across development teams, like availability, with a more immediate ROI. Delegating responsibility to a single platform/FinOps team leaves many optimisations off the table, and may elongate projects.

- 💻 Developer tooling and AI can shift a lot of effort left. Producing code will become less of bottleneck as more of this responsibility is delegated to machines. However, understanding how that code impacts system reliability and costs will only matter more over time.

- 🔐 “Lock-in” and cloud commitments get a bad reputation, because it’s harder to quantify the opportunity cost of not going “all-in” on providers’ offerings.

As always, context matters, so the next time we see a headline about an organization’s hosting costs, it’s worthwhile treating it with the nuance it deserves, rather than being outraged by the headlines.

Get in touch 📧

As I say in my About page, I would love to hear from you. If you got to the end of this post and have anything to share, please get in touch on LinkedIn or Twitter.

In future posts, I may dive into some neat cost management measures I have seen in the wild. In the meantime, here are a few podcast recommendations: